Urban Deprivation and Inequality

Deprivation refers to the extent to which a community or individual lacks access to essential amenities and services. Deprivation can be measured by:

- education (no one in a household has at least level 2 education, and no one aged 16-18 years is a full-time student)

- employment (if any member, not a full-time student, is either unemployed or economically inactive due to long-term sickness or disability)

- health (if any person in the household has general health that is bad or very bad or is identified as disabled)

- housing (if the household’s accommodation is either overcrowded, in a shared dwelling, or has no central heating)

Deprived communities often have high population densities, congested roads, few parks and shops, and experience high levels of unemployment and crime.

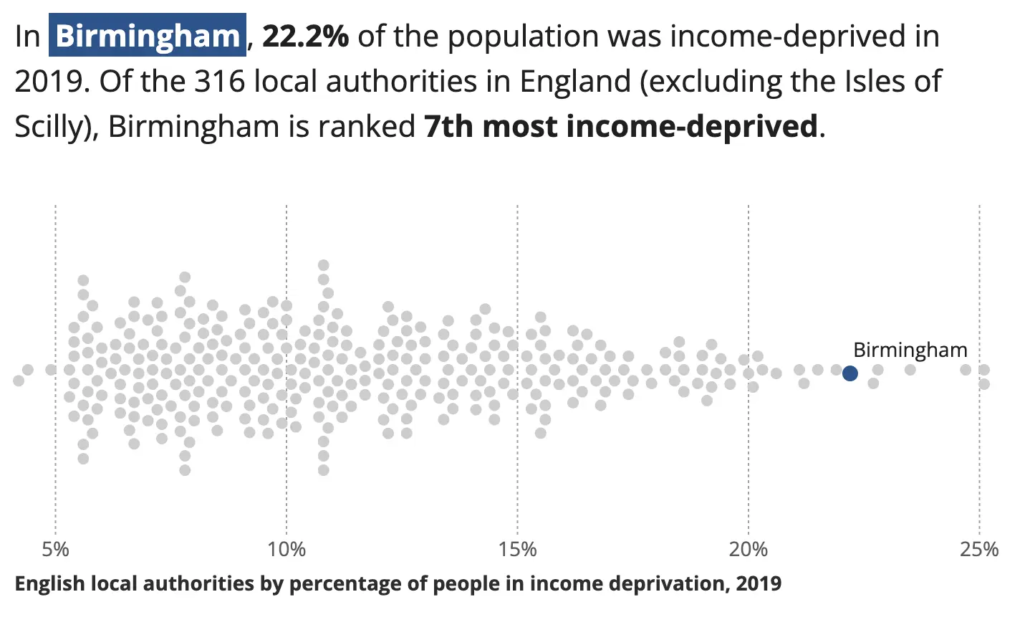

Like many large UK cities, Birmingham faces significant social and economic challenges due to rapid urban change. Deprivation remains a key issue, with areas of the city experiencing multiple disadvantages in income, employment, health, education, housing, and crime. According to the 2019 Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), Birmingham is the 7th most deprived local authority in England. 22.2% of its population was income deprived in 2019. 40% of its neighbourhoods ranked among the most deprived 10% in the country.

Income deprivation in Birmingham – source https://www.ons.gov.uk/visualisations/dvc1371/#/E08000025

Inner-city wards such as Ladywood, Sparkbrook, and Washwood Heath suffer from high unemployment, low educational attainment, and poor health outcomes. In contrast, suburbs such as Sutton Coldfield and Edgbaston are far more affluent. These inequalities reflect the long-term impacts of deindustrialisation, combined with recent population growth and housing pressures.

Birmingham has the 4th largest income gap between the most and least income-deprived neighbourhoods of all local authorities in England. In the least deprived neighbourhood, 1.3% of people are estimated to be income deprived. In the most deprived neighbourhood, 55.8% of people are estimated to be income deprived.

The map below shows household deprivation in four dimensions (education, employment, health, and housing) in Birmingham’s wards.

Housing Inequality

Birmingham has a shortage of affordable and high-quality housing. Many households are overcrowded, particularly in inner-city areas with high numbers of recent migrants. Birmingham City Council has the largest local authority housing stock in the UK, yet demand continues to outstrip supply. Waiting lists for social housing remain lengthy, and housing inequality is on the rise.

Private rents are also rising. According to the ONS, average private rents in Birmingham increased by 6.1% between 2022 and 2023, making it harder for low-income families to afford accommodation. The city’s housing challenges are particularly acute for young people and vulnerable groups.

Education and Health Inequality

Educational attainment in Birmingham varies widely. While some schools, particularly in suburban areas, perform above the national average, others in more deprived wards struggle with poor outcomes. According to the Department for Education, the percentage of pupils achieving a grade 5 or above in English and Maths GCSEs in Birmingham was 45.8% in 2022, slightly below the national average.

The map below provides an overview of educational attainment in local authorities in England and Wales based on the 2021 Census. By selecting Birmingham, we can see an overview of the city.

Once selected, we can see that Birmingham had a lower average qualification rank than 81% of local authorities.

Health inequalities are also significant. Life expectancy in deprived areas of Birmingham is several years lower than in wealthier parts of the city. Air pollution, overcrowded housing, and limited access to green space contribute to these disparities. The city also faces high rates of obesity, diabetes, and respiratory illnesses.

By selecting Birmingham as an area on the map below, we can see that life expectancy in the city is lower for both males and females compared to the national average.

Inequalities in Employment

The number of people claiming unemployment-related benefits in the West Midlands was highest in Birmingham in 2024. 9.1% of people aged 16-64 years in Birmingham claimed unemployment-related benefits. The average for England and Wales in March 2024 was 4.6%.

At the time of the 2021 Census, 39.1% of people aged 16 years and over were economically inactive. This figure was higher in Birmingham, where 44.4% of the population was economically inactive. The map below shows the proportion of people economically inactive in Birmingham’s geographic areas. Central areas generally had a higher proportion of economically inactive people. Saltley East has the highest proportion of people who were economically inactive at 56.2%.

Birmingham’s Environmental Challenges

Urban change in Birmingham has brought many benefits, but it has also created a number of environmental challenges. These challenges stem from its industrial past, population growth, and ongoing development pressures. Key environmental issues include dereliction, the use of brownfield and greenfield sites, and waste management.

Dereliction

Following the decline of Birmingham’s traditional manufacturing industries in the late 20th century, large parts of the inner city were left derelict. Former factories, workshops, and warehouses—especially in areas like Digbeth and east Birmingham—became underused or abandoned. While many of these sites have since been redeveloped (e.g. the Custard Factory and Eastside), others remain in poor condition, contributing to urban blight and antisocial behaviour.

According to Birmingham City Council, there are still over 100 hectares of brownfield land within the city boundaries awaiting redevelopment. These areas can attract crime and vandalism if not properly managed or regenerated.

Building on Brownfield and Greenfield Sites

Brownfield sites (previously developed land) offer sustainable development opportunities but often require significant clean-up due to contamination from past industrial use. This can be expensive and time-consuming. Despite this, Birmingham has prioritised brownfield development as part of its urban planning strategy. Projects like the Smithfield redevelopment and Eastside expansion are examples of brownfield regeneration.

In contrast, greenfield sites (undeveloped land, often on the urban fringe) are easier and cheaper to build on but raise environmental concerns. They can result in the loss of green space, habitats, and agricultural land. For example, plans to develop housing in parts of Sutton Coldfield and along the southern edge of the city have been controversial, facing opposition from local residents and environmental campaigners.

Waste Disposal

Birmingham faces significant waste management challenges due to its large and growing population. The city produces over 400,000 tonnes of household waste per year. While recycling rates have improved slightly, they still lag behind the national average. According to DEFRA data, only 23.4% of Birmingham’s household waste was sent for reuse, recycling, or composting in 2022, compared to the national average of around 44%.

Much of the city’s residual waste is processed at the Tyseley Energy Recovery Facility, which incinerates waste to generate electricity. However, this method still contributes to air pollution and carbon emissions, raising questions about its long-term sustainability.

How has Birmingham’s urban growth led to urban sprawl?

Urban sprawl refers to the outward expansion of a city into surrounding rural areas. In Birmingham, decades of population growth, housing demand, and infrastructure development have led to significant urban sprawl, particularly towards the north (Sutton Coldfield), south-west (Northfield and Longbridge), and into surrounding areas of Solihull and the Black Country.

Several factors have driven this growth:

- Population increase: Birmingham’s population rose from 977,087 in 2011 to over 1.14 million in 2021 (ONS), with further growth expected.

- High land prices in the city centre and competition for space with commercial, office, and leisure developments make city-centre housing less affordable.

- Pressure on brownfield sites has pushed housing development into less densely populated greenfield areas on the outskirts.

- Improved transport infrastructure such as extensions to the West Midlands Metro and road improvements have made it easier for people to live further out and commute in.

- Lifestyle preferences, particularly for families, have increased demand for quieter, greener suburban and semi-rural locations.

Birmingham’s Development Plan (BDP 2031) anticipates a shortfall of 37,900 homes within the city boundary and therefore proposes building on the Green Belt, including up to 6,000 homes on land near Sutton Coldfield.

What is the impact of urban sprawl on the rural–urban fringe?

The rural–urban fringe around Birmingham has seen significant transformation. Areas such as Walmley, Rubery, and the eastern edges of Solihull have seen the development of new housing estates, expanded road networks, and commercial growth. This has led to:

- Loss of greenfield land has caused concern among environmental groups and residents.

- Increased congestion and air pollution, particularly on key routes into the city such as the A38, A34, and M6.

- Reduced biodiversity, as urbanisation puts pressure on wildlife habitats and green corridors.

The West Midlands Green Belt has been under pressure, with local protests over proposed developments. For example, residents have opposed the Langley Sustainable Urban Extension (near Sutton Coldfield), which proposes building up to 5,500 homes, schools, and transport links.

Air Pollution and the Clean Air Zone

Air quality remains a major concern, particularly in the city centre and along major roads such as the A38 and the A4540 ring road. The main sources of pollution are vehicle emissions and industrial activity. According to the ONS, parts of Birmingham regularly exceed WHO air quality guidelines for nitrogen dioxide (NO₂). According to Public Health England, poor air quality contributes to over 1,000 premature deaths each year in the city.

To address this, the city introduced the Clean Air Zone (CAZ) in June 2021. The CAZ charges older, more polluting vehicles to enter the central area, aiming to reduce emissions and improve public health. Early data suggest a 13% reduction in NO₂ concentrations in the zone. However, concerns remain about traffic displacement into surrounding residential areas, especially during peak hours. Vulnerable groups, including children and those in deprived areas, remain disproportionately affected.

The growth of commuter settlements

Urban sprawl and rising property prices have encouraged the growth of commuter settlements outside Birmingham. Towns such as Redditch, Tamworth, Lichfield, and Bromsgrove have become increasingly popular among people working in Birmingham.

Several factors contribute to this trend:

- Improved rail links from towns like Lichfield and Tamworth allow residents to reach Birmingham New Street in under 30 minutes.

- The expansion of the motorway network, including the M5, M6, and M42, enables faster car commuting.

- New housing developments in areas such as Longbridge and the southern fringe of Solihull attract professionals priced out of central Birmingham.

While this relieves housing pressure in the city, it also increases car dependency, contributes to rural land loss, and places pressure on services in outlying towns. It also risks exacerbating social inequality, as higher-income residents move to more desirable commuter areas.