How has urban change created challenges for Bristol?

What are the social and economic challenges resulting from urban change?

Urban change in Bristol has brought various social, economic and environmental challenges.

Urban Deprivation

Deprivation is the degree to which a community or individual is deprived of amenities and services. Deprivation can be measured by:

- education (no one in a household has at least level 2 education, and no one aged 16-18 years is a full-time student)

- employment (if any member, not a full-time student, is either unemployed or economically inactive due to long-term sickness or disability)

- health (if any person in the household has general health that is bad or very bad or is identified as disabled)

- housing (if the household’s accommodation is either overcrowded, in a shared dwelling, or has no central heating)

Deprived communities often have high population densities, congested roads, few parks and shops, and experience high levels of unemployment and crime.

Urban Deprivation in Bristol

According to the 2021 Census, 31.8% of households are deprived in one dimension (from education, employment, health, or housing).

15.6% of the city’s population lives in some of the most deprived areas in England. Some of the most deprived areas of Bristol are close to the city centre and in the south of the city.

Following Second World War bomb damage, many residents from the inner city were relocated to the southern suburbs of Withywood, Filwood, Whitchurch Park and Hartcliffe. Today, many council-run estates and high-rise flats need modernisation. These areas experience high levels of crime and unemployment.

Inequalities in Housing

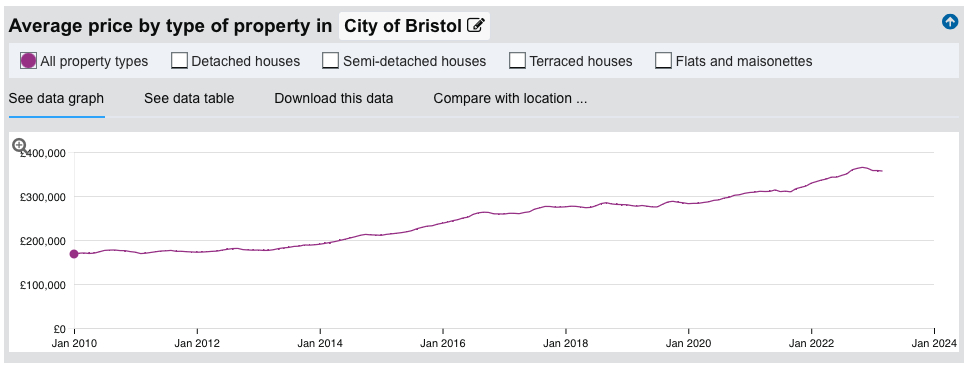

The demand for housing in Bristol has seen house prices rise significantly between 2010 and 2023. In 2010, average house prices were £168050. However, this more than doubled by January 2023, when average prices reached £356686 (source – HM Land Registry)

Bristol has a relatively high proportion of local authority housing, with 13% of the housing stock owned by the local authority compared to the average for England, which is 6%. However, in 2023, almost 17,000 families were on the waiting list for council housing. The problem is particularly high in the south of the city where many want to move from properties that are run down and need modernisation. There is also a lack of social housing, with only 6% of Bristol’s properties owned by private registered providers of social housing (e.g. housing associations) compared to 10% across England.

Bristol has the highest rate of homelessness in the southwest of England. It was estimated that 1972 people were homeless in the city in 2021. Bristol is in the top 20% across England for the rate of people recorded as homeless as a proportion of the population.

The high number of students studying at Bristol’s two universities has increased pressure on housing, especially for rental properties.

Inequalities in Education

The data below provides an overview of educational attainment in local authorities in England and Wales based on the 2021 Census. By selecting Bristol, we can see an overview of the city. The data shows that Bristol is one of England and Wales’s most highly qualified areas. This is largely due to the high proportion of residents with a level 3 (A level or equivalent) and level 4 (a degree or equivalent) qualification. This is partly due to the presence of the two universities and the influx of graduates to work in Bristol’s growing high-tech industry sector.

It is worth noting that this data hides inequality within Bristol. Deprived areas such as Highridge, Withywood and Hartcliff have very low higher education attainment rates. More affluent areas like Cotham have a much higher participation rate.

Despite the above-average proportion of people having achieved a degree, the proportion of students achieving level 1 and 2 qualifications is below the national average. The city’s Progress 8 (GCSE) score was close to the England average. However, Bristol also experiences considerable inequalities in educational attainment. Students living in the most deprived areas of Bristol typically experience lower levels of attainment than more wealthy districts. In 2022, the achievement of children living within the most deprived 10% of the population was amongst the lowest in Bristol. In contrast, the performance was much better for children living in the 10% least deprived areas.

Inequalities in Health

Urban change has posed difficulties for the healthcare sector due to disparities in wealth throughout the city. Less affluent neighbourhoods such as Hartcliffe and Withywood, Filwood and Lawrence Hill record higher levels of poor health and lower life expectancy, coupled with an increased incidence of premature death. These regions also struggle with prevalent obesity and smoking rates. Conversely, more affluent wards like Clifton and Redland enjoy better health conditions and life expectancy, with notably fewer instances of early mortality.

Inequalities in Employment

In 2022, Bristol’s employment rate was 82.5%, the fifth highest of all UK cities.

However, there are significant inequalities with high levels of unemployment in the south of the city and close to the city centre. The map below shows differences in unemployment rates across Bristol.

Areas with low educational attainment typically have higher levels of unemployment, such as Highridge, Withywood and Hartcliff.

Bristol’s Environmental Challenges

Urban change in Bristol has created a range of environmental challenges. These are mainly the result of Bristol’s rapidly growing population and changing industry. The challenges include:

- buildings used for industry becoming derelict

- new developments being constructed on brownfield and greenfield sites

- waste disposal

Dereliction

Bristol has witnessed a downturn in the industry linked to its harbour and railway hub roles. The evolution towards a post-industrial economy, driven by high-tech and various service industries, has resulted in numerous warehouses and historical buildings falling into disrepair. Previous industrial zones may be contaminated with hazardous materials, which are costly to decontaminate and make safe for other use.

The areas that have become rundown have been mainly concentrated in the city centre. Industrial buildings associated with the port of Bristol have declined since the port moved to Avonmouth in the 1960s to accommodate larger containerships. Many industrial buildings and warehouses fell into disrepair when they were abandoned.

Building on brownfield and greenfield land

A brownfield site refers to land previously used for development, while a greenfield site signifies untouched land, usually on the outskirts of urban regions. Urban transformations such as deindustrialisation or the dismantling of substandard housing lead to the creation of brownfield sites. Preparing a brownfield site for redevelopment presents expensive challenges, such as waste clearance, land decontamination, and establishing contemporary infrastructure like water, electricity, and internet access. Finzels Reach exemplifies a successful brownfield site redevelopment, transforming into a thriving waterfront area with offices, shops, restaurants, and apartments.

On the other hand, greenfield sites necessitate less preparation work, making them appealing to developers. However, greenfield developments often face opposition, and securing planning permissions can take considerable time. In Bristol, from 2015 to 2020, only around 5 per cent of new housing developments were on greenfield sites.

The most substantial greenfield development, located just north of Bristol, is the town of Bradley Stoke, which was established in the 1980s. Recent proposals for new housing developments to house the growing population have sparked resistance from local residents and environmentalists, raising concerns over potential traffic congestion and impacts on local ecosystems and habitats.

Waste disposal

The population of Bristol is expanding at roughly 1 per cent annually, and dealing with household waste and debris from clearing deteriorated land poses a significant hurdle. There’s a shortage of landfill sites, and alternative solutions like incineration plants produce greenhouse gases.

Efforts to minimize waste, such as recycling and minimizing packaging, have successfully decreased the volume of domestic waste by around 8 per cent per year, lowering it to approximately 462 kg per household in 2019. Despite these advances, the city still produces about 140,000 tonnes of garbage yearly. The unrecyclable waste, roughly 54,000 tonnes, is transported to a Mechanical Biological Treatment plant at Avonmouth. This facility converts food waste into biogas rich in methane, which is then used to generate electricity.

How has Bristol’s urban change led to urban sprawl?

The escalating population of Bristol, coupled with the demolition of old slum housing, has increased demand for new accommodation. The city suffered significant damage during the Second World War, with more than 3,200 houses destroyed and 1,800 severely damaged.

New council homes were constructed in southern suburbs such as Whitchurch Park, Hartcliffe and Withywood, and Filwood. Private housing development also increased, expanding the city’s boundaries.

This outward physical growth of a city is known as urban sprawl. In Bristol, it has led to the city’s expansion towards both the south and north. For instance, the establishment of the new town of Bradley Stoke, situated roughly 9 km northeast of the city centre, has extended the city into South Gloucestershire.

Several factors in Bristol have contributed to urban sprawl as a result of urban change:

- The city’s rapidly growing population, primarily driven by migration from within the UK and overseas

- The scarcity of affordable housing in the city centre

- A competitive demand for land on brownfield sites in the city centre (for industrial, retail, and office uses) led to a steep rise in land prices

- Upgrades to transport infrastructure, facilitating easier commuting into the city centre • A preference among many people to reside in quieter, less polluted semi-rural areas.

What is the impact of urban sprawl on the rural-urban fringe?

The construction of extensive housing estates, motorways, and service infrastructure at the rural-urban fringe has sparked controversy. Local residents and environmentalists have expressed worries about the loss of rural landscapes and the effects on wildlife biodiversity and habitats. Increasing traffic congestion levels, noise, and air pollution are also areas of concern.

In response to the rapid urban sprawl jeopardising the two cities’ autonomy, the Bristol and Bath Green Belt was established in 1966. Currently, the green belt covers a vast area. Due to stringent planning regulations, land within the green belt is safeguarded from new developments, such as housing and industry.

While the green belt’s rigorous planning rules provide some protection, they do not cover the entire rural-urban fringe. Several developments have taken place on lands that were once open countryside, including:

- Transportation links around the city, encompassing the M32, M4, M5, and M49 motorways.

- The out-of-town retail park at Cribbs Causeway is located adjacent to the M5.

- Modern industrial estates, such as Aztec West, are situated near the M4-M5 junction.

- Leisure facilities such as Ashton Court golf course and other related developments.

Housing developments at Harry Stoke

Harry Stoke, a quaint village near the junction of the M4 and the M32 northeast of Bristol, is the focus of a proposal by the South Gloucestershire Council to construct 1,200 homes. This is an attempt to address the area’s housing shortage. However, the proposal has faced significant opposition from local residents who believe the development will amplify noise and traffic congestion, damage local habitats, and elevate the risk of flooding. Moreover, the potential loss of open spaces and rural landscapes may adversely affect residents’ mental well-being.

The growth of commuter settlements

Commuter settlements refer to areas where many residents travel to work in different locations. In the case of Bristol, the city sees more incoming commuters for work than those leaving for jobs elsewhere. While many commuters reside in the immediate rural-urban fringe, others cover considerable distances, opting to live in places like Weston-super-Mare in Somerset and South Gloucestershire.

Towns such as Clevedon in North Somerset and Wotton-under-Edge in Gloucestershire have become popular commuter settlements. Following the abolition of the Severn Bridge tolls in 2018, more people are opting to live in South Wales, where the cost of property is generally lower.

Related Topics

Use the images below to explore related GeoTopics.