Helping Students Tackle the 2025 AQA GCSE Geography Pre-Release: Strategies for a Challenging Text

Practical strategies for helping students overcome literacy challenges to tackle the 2025 AQA GCSE Geography Pre-Release.

Practical strategies for helping students overcome literacy challenges to tackle the 2025 AQA GCSE Geography Pre-Release.

Developing knowledge organisers for AQA GCSE geography units provided a stark reminder of the sheer number of geographical terms students need to understand to be successful in geography. As a result, I have included seventy-four key terms for the documents covering River Landscapes in the UK alone.

AQA has produced a document containing key terms and definitions for each GCSE geography unit. However, it falls short of including all the terms students need to know. When adding vocabulary to the knowledge organisers, it reminded me of the significant number of tier three literacy terms students need to be able to use. It also made me reflect on my time in the classroom and that, in all honesty, I didn’t do enough to teach these critical terms to my students explicitly. I think I probably got in the comfort zone where I assumed students would know and be able to use these terms.

The Geographical Association provide a reminder of the importance of literacy in geography.

“The use of language is an integral part of learning geography, and literacy skills are essential for geographical understanding. It is through language that students develop their ideas about geography and communicate them. “

Rather than consider literacy as a discrete element, literacy should be a foundation of geographical education, including the explicit instruction of tier three vocabulary.

“Literacy in secondary school must not simply be seen as a basket of general skills. Instead, it must be grounded in the specifics of each subject. Crucially, by attending to the literacy demands of their subjects, teachers increase their students’ chance of success in their subjects. Secondary school teachers should ask not what they can do for literacy, but what literacy can do for them.”

Education Endowment Foundation – Improving literacy in secondary schools

Many learners may struggle with tier 3 (subject-specific) vocabulary as it is often unfamiliar. A Year 8 student, for example, will rarely see ‘gross national product’ or ‘tributary’ in their wider reading.

Learners who can’t understand subject-specific terminology can’t access the taught content. Fortunately, content and vocabulary don’t have to be separate entities.

Identify key terms – Available in PPT format to Internet Geography Plus subscribers.

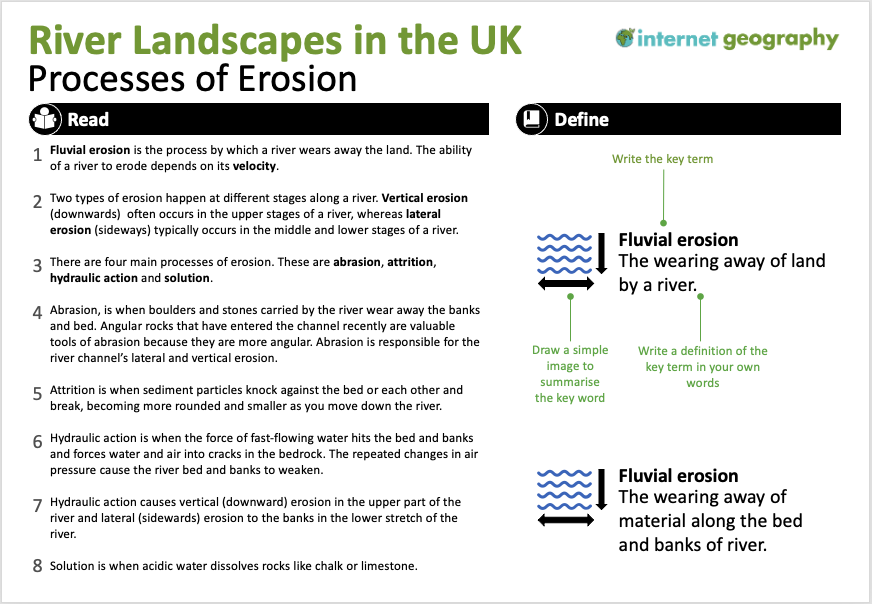

Images and definitions – A downloadable PPT of this is available to Internet Geography Plus subscribers.

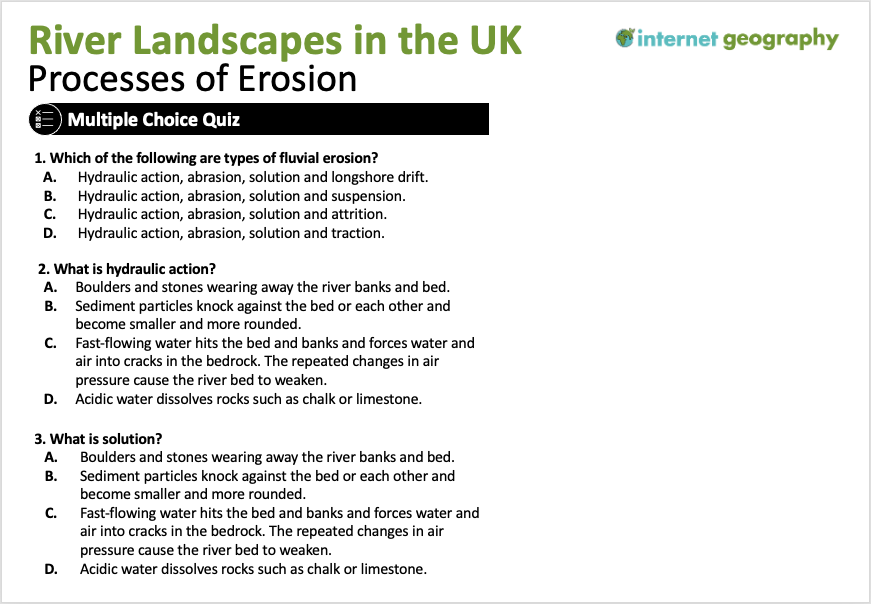

Low-stakes quizzes – Internet Geography subscribers can access this slide in PPT format.

Internet Geography Plus subscribers can access a significant bank of multiple-choice booklets, and Google/Microsoft forms multiple-choice quizzes.

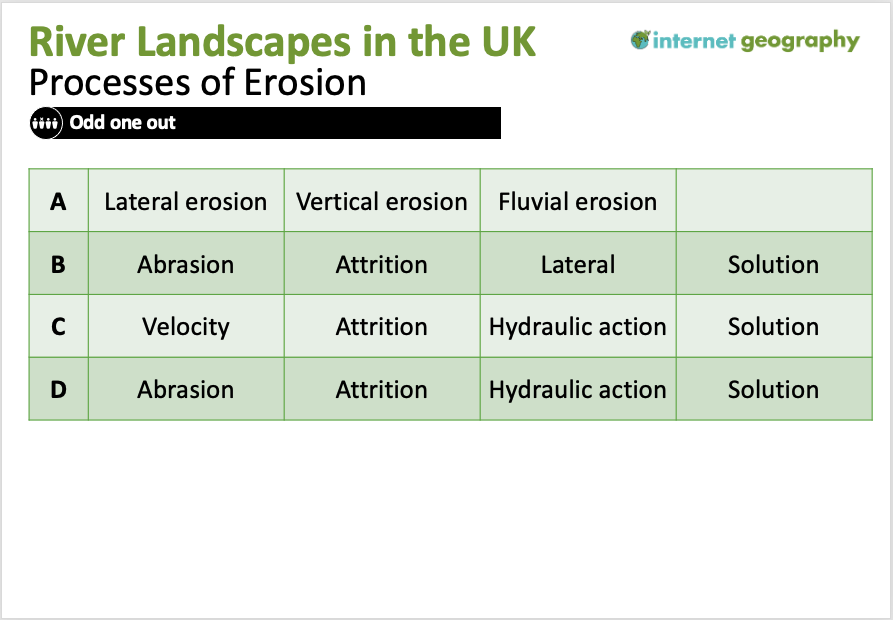

Odd one out

Internet Geography Plus subscribers have access to a collection of odd one-out activities.

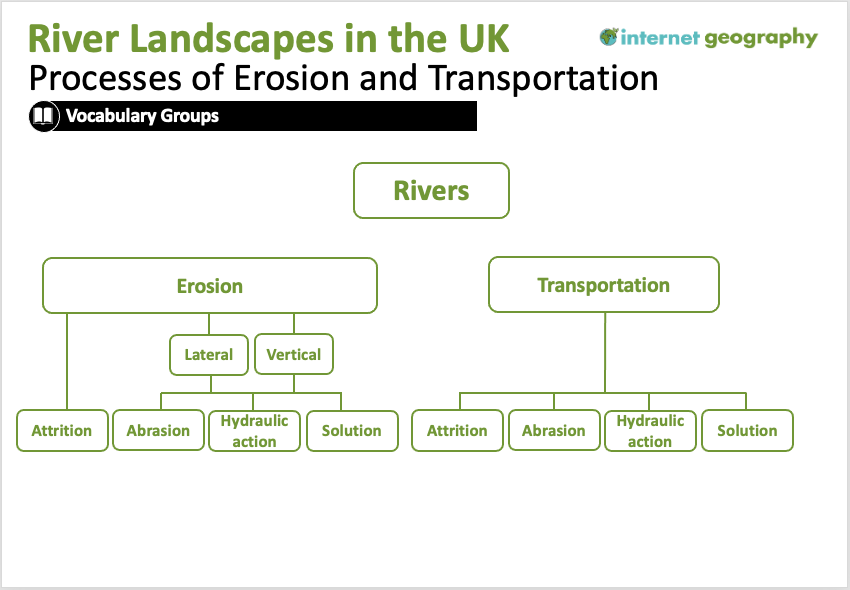

Vocabulary groups

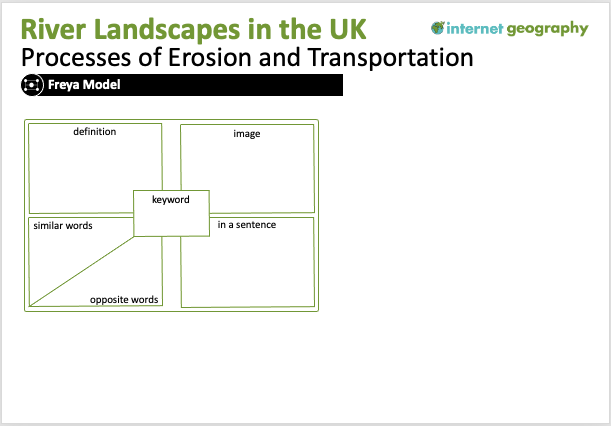

The Freya Model in geography.

A template for the Freya Model is available in an editable PPT format to Internet Geography Plus subscribers.

You can learn more about the Freya model on Alex Quigley’s blog.

Students must regularly revisit these key terms to be committed to their long-term memory. Therefore retrieval practice activities will be essential over the long term.

If you’ve successfully used a strategy to support teaching geographical vocabulary, please join the discussion and let us know below!

We’re really pleased that guest blogger, Abdurrahman Pérez (@mr_perez5), is back discussing his strategies for encouraging students to develop their answers to geographical questions further.

My biggest takeaway having finished my second year in the classroom was how often I was finding students were leaving arguments/points half-done, undeveloped and leaving me asking “so?”, “and?” or “why?”. I was writing these three questions on student work so often I thought I had to do something about it. So much was it a worry for me that when I finally put up the display on it (which I’ll get back to later), I began every lesson introducing it, telling all my classes where the display was, why I had made it and how they could use it. My thoughts on being honest with pupils are perhaps for another time, but I cannot overstate its importance – why let them be mind-readers? Tell them what you want from, why you do what you, why you’re approaching a lesson a certain way, etc… Anyway, that’s for another time!

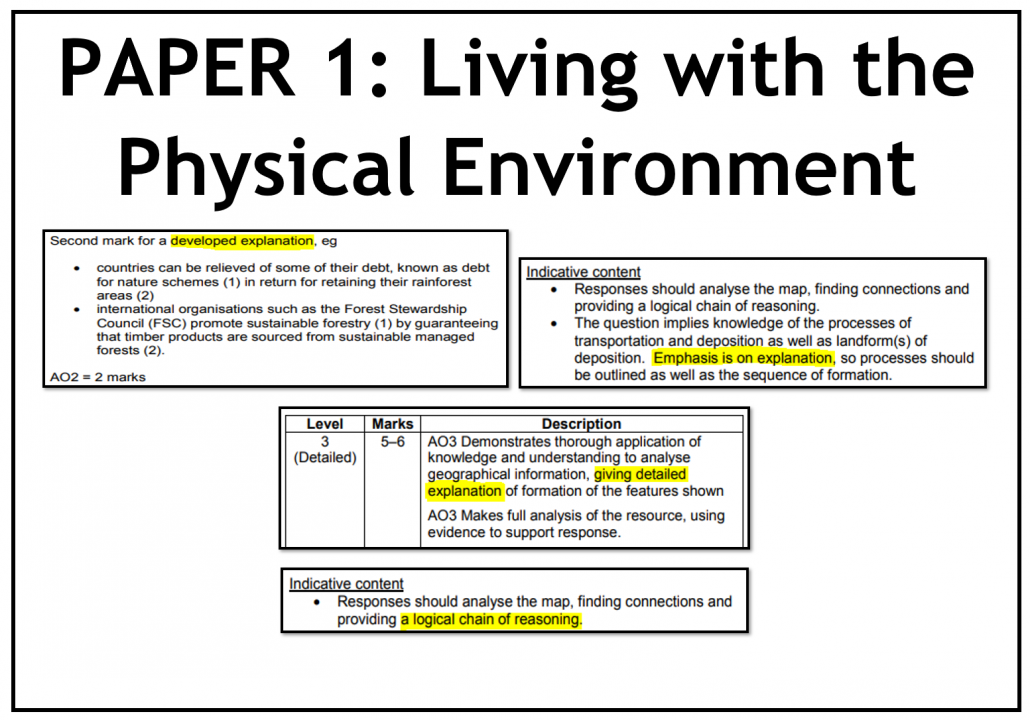

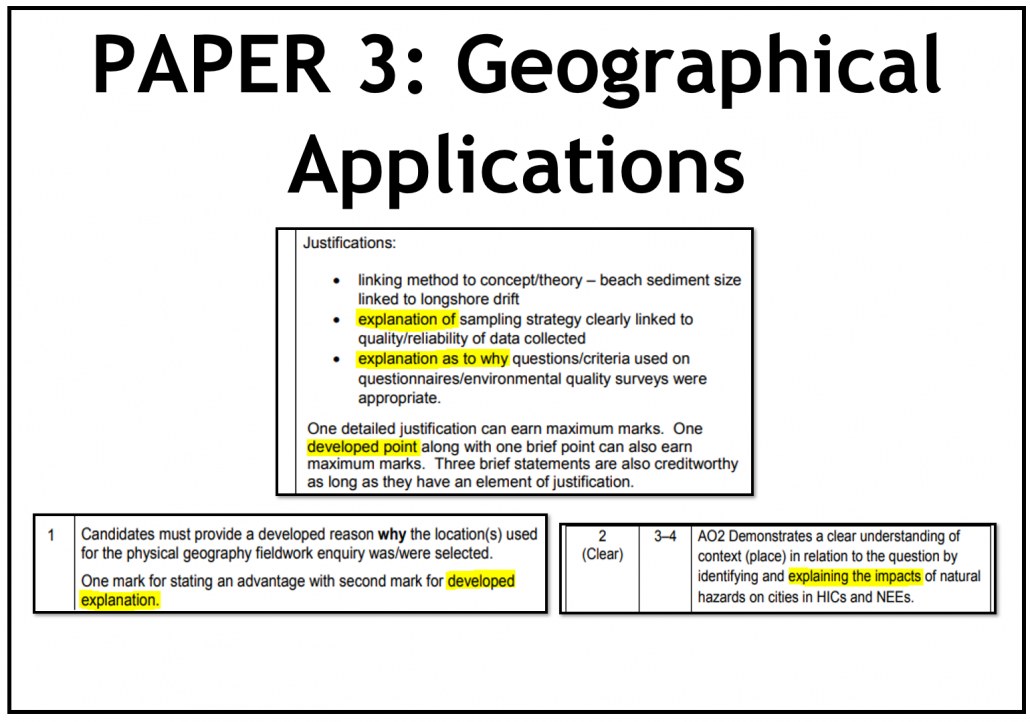

The AQA mark schemes want “developed” responses, so does Edexcel (as well as “logical connections”) and Eduqas call them “chains of reasoning”, a much better way of thinking about it, but my thoughts on why Eduqas is infinitely better than AQA and all the rest deserve a whole book, so I’ll leave it there!). Below you can see some AQA examples, which I decided to keep out of the final display as they are unnecessary and made it far less student-friendly. The urge to address this was further compounded when I recalled some of my Year 11s scripts from the summer exams and noticed how ‘highly-rated’ the approach of elaborating and explaining themselves my pupils had used to good effect was. (This would later be confirmed when I did some exam marking over the summer and noticed how successful candidates who properly developed their answers were.

Paper 1 Living with the physical environment

Paper 3 Geographical Applications

In my department, we start everything from KS3, not in the exam-factory sense, but more in a bid to get the right skills embedded by the time students get to Year 10 when we start our two-year GCSE. This means I wanted everyone to be elaborating and developing their points, from 7 set 5 to my Year 13s. In my opinion, this approach is totally applicable to all ages and abilities – in fact, my explanation of the display was no different with 17-year-olds than it was with 12-year-olds…

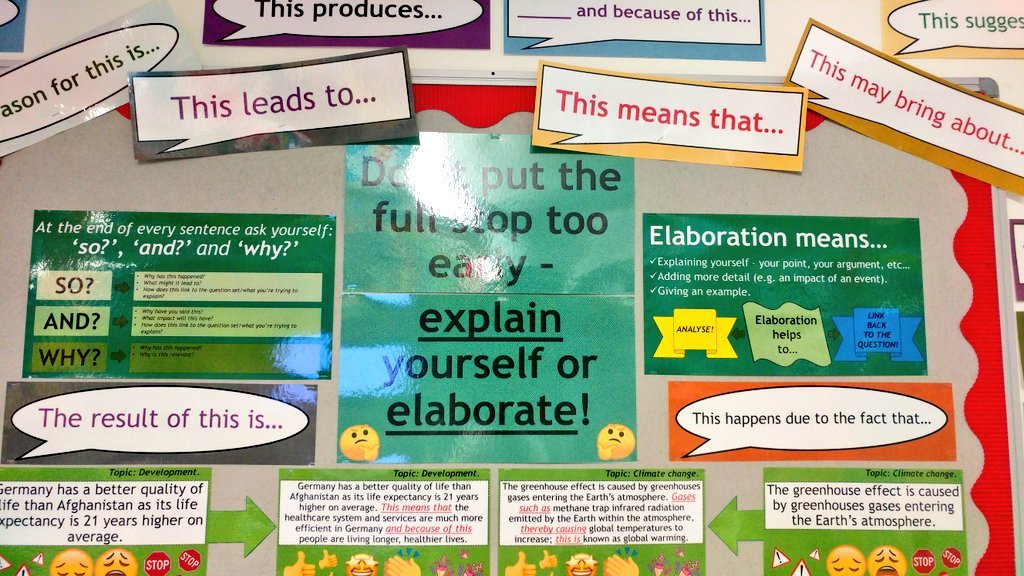

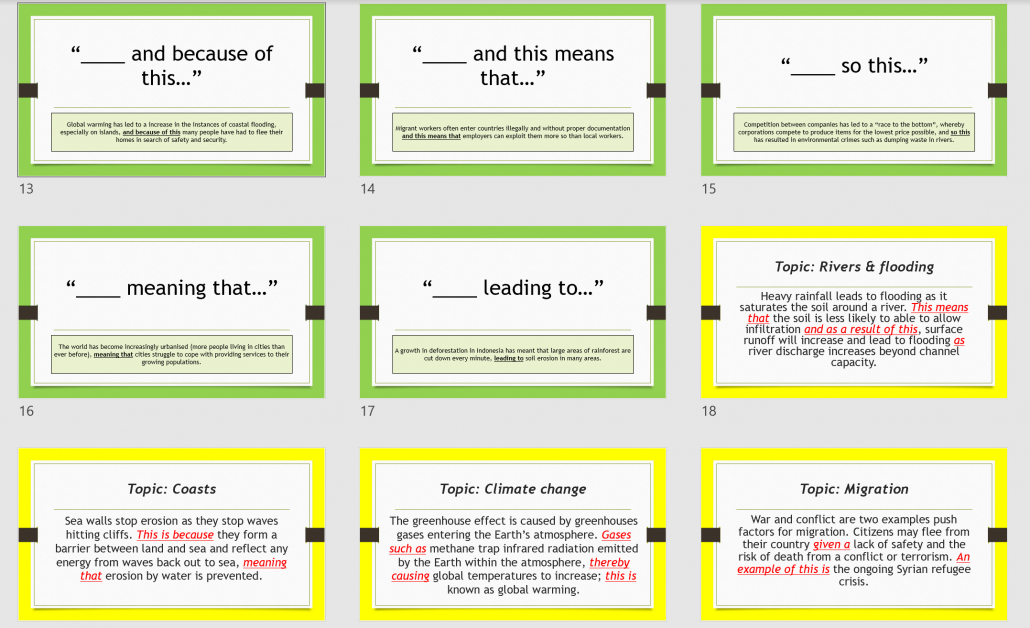

I call it “don’t put them full stop too early” – I want my pupils to elaborate on their evidence, explain their arguments or develop their points. This concept is at the heart of acronyms such as PEEL, PEDaL, etc, so chances are you are aiming for it too. I don’t want: “heavy rainfall leads to flooding as it saturates the soil around a river” – I want “heavy rainfall leads to flooding as it saturates the soil around a river. This means that the soil is less likely to able to allow infiltration and as a result of this, surface runoff will increase and lead to flooding as river discharge increases beyond channel capacity.” Yes, the sentence is longer but now I know that the pupil knows their stuff and I expect this from Year 7s, mind. I tell my pupils that I know and trust they know their stuff (most of them at least!), they just need to prove it because I won’t assume anything when I’m marking their work or questioning them in class; for the older ones, I tell them to prove it to an examiner who has never met them. To help them do this, my pupils are presented with a number of stems.

Wall display to support elaboration

Explain yourself or elaborate

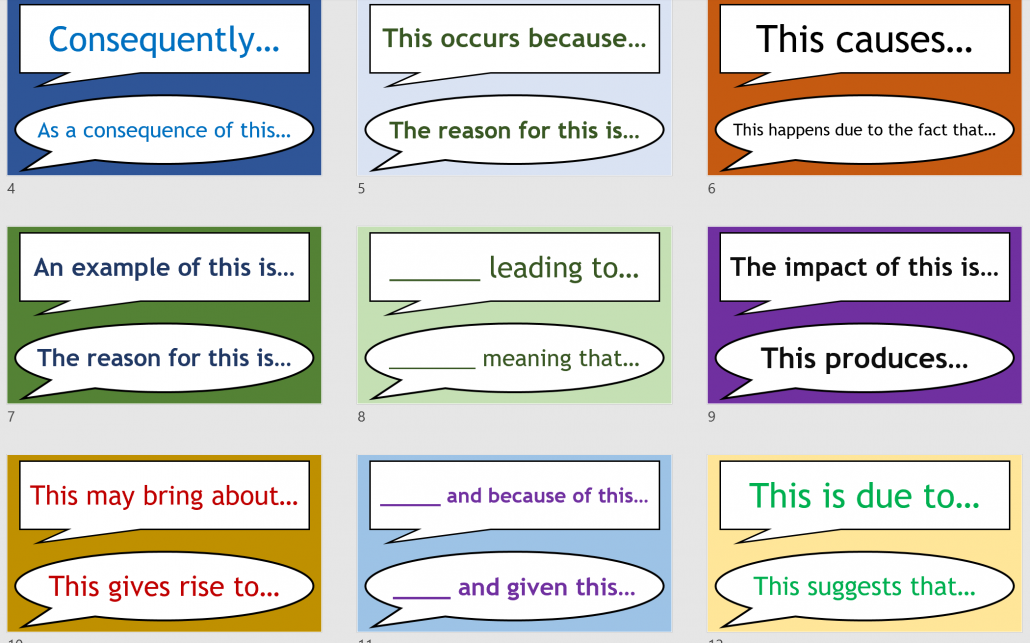

Writing cues

The display:

I am not interested in wading into the whole “what is the point of displays?” ‘debate’ that has cropped up on Twitter an annoying amount of times. Am I covering exactly 44.56% of my walls? I don’t know. Am I complying with fire-safety rules? I’m not sure…(?). Am I distracting pupils? I sure hope not…

What matters is that this display works with for me and I use it very often for the benefit of my pupils. That is all that does and will ever matter in the display debate. I am often directing students to its use and I encourage students to look at it whilst completing in-class extended writing (we call them Big Writes) and I even get them to use them whilst stretching their verbal responses to my question. For example, if a pupil has given me an answer and I want more from them, I will challenge them to turn around and use one of the stems to extend their answer. Or I might get another pupil to do this for them.

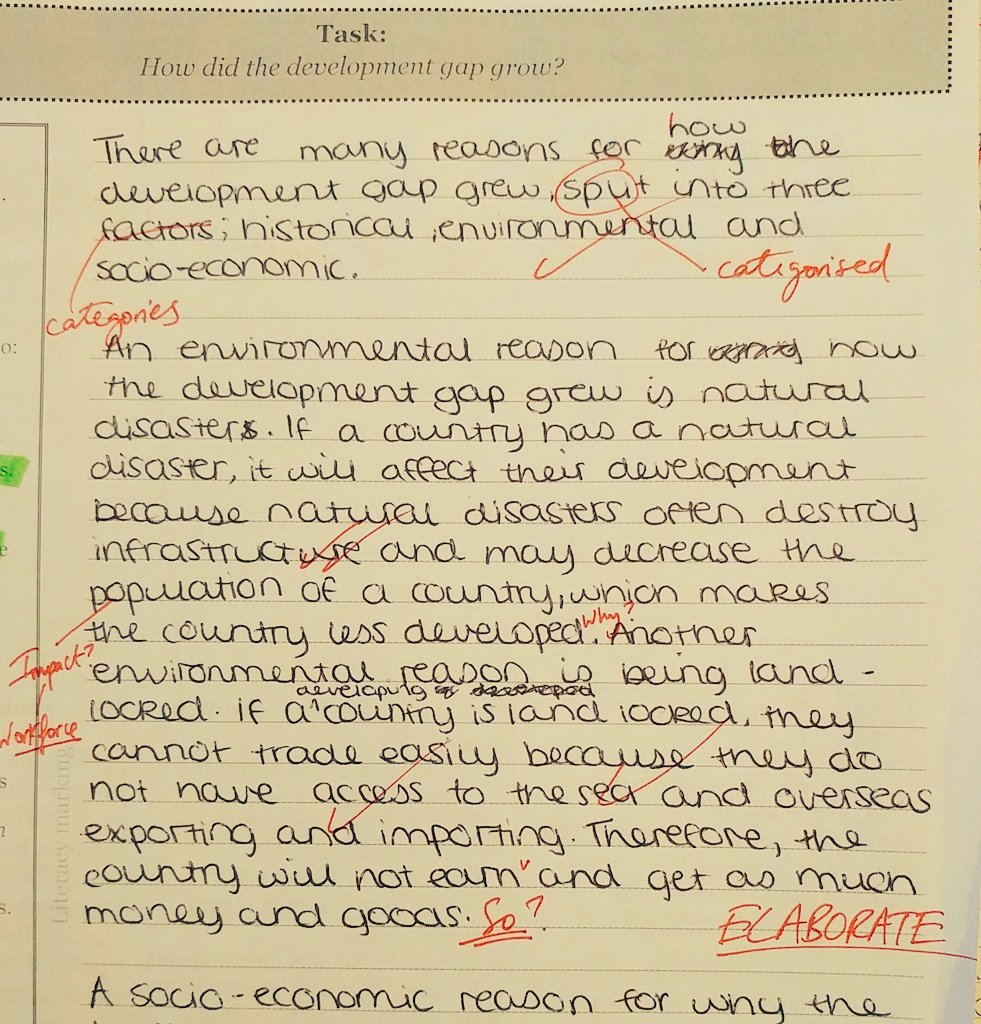

This led to some good results here and there – this year 9 pupil you can see is in the process of grasping it:

Example of response

However, this is still a developing approach and is by no means embedded. I need to model it for pupils more often and maybe even the fact that the display is at the back of my class makes its use impractical. This is partly the reason why I have created laminated cards. Inspired by @missgeog92, these will be placed into the boxes I have on my desks which currently house the glues, scissors and dictionary, held together using some cheap binding rings from Amazon.

And this means that…

This results in

Writing cues and examples

What matters really is how much I push them. I, and you if you decide to use them, cannot just hope pupils will diligently pick them up during a lesson and just use them. After all, how many of them use those nice laminated matts you put out every so often? Pupils need training and modelling, so that’s my task in September. Hopefully, if I do it often enough it’ll stick! It’s easy to want rapid results but you and I know that’s not how teaching works – it’s not how children (and their brains) work! To ‘convince’ them I have often used lots of written and verbal examples, I praise its use pupils and I often refer to the actual display in lessons, getting the whole class to turn and face it – much to the chagrin of moody teenagers! However, what I think really struck a chord with some – and to return to my point of being honest with students – is when I explained why they should use the display.

I told/tell them elaboration can mean: (1) explaining yourself – your point or your argument; (2) adding more detail (e.g. an impact of an event) or (3) giving an example. I tell them it can help to analyse (the A-Level lot love this) or a way to link back to the question (and the GCSE classes lap this up!). I ask them to ask themselves the very same questions I am left asking when I’ve read their work: So? And? Why? That’s when a lot of them ‘get it’.

I think we’re all trying to do this in some sort way – in fact, I initially thought this might be a good blog post because I saw @Geoisamazing’s brilliant “This means that…” resource recently on Twitter and it reminded me of what I had done/was planning to do. It is definitely a case of ‘slowly, slowly catchy monkey’ (very slowly with some pupils or classes), but it’s certainly worth sticking with. You’ll notice differences in oral responses as well written answers in time and that will mean you will have equipped your pupils with the tools to produce work you – but more importantly, they – can be very proud of!

Abdurrahman Pérez (@mr_perez5)

August 2019

You can find the elaboration display here and I will post the laminated ring cards on my Twitter account when they’re finished: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1_ufOduWmtrdd-zxwKw3RBWg-DimRU4CL?usp=sharing

Internet Geography is offering a platform for guest bloggers for this academic year. Got a teaching strategy, interest or anything geographical you’d like to share? Please contact us. We’re unable to offer a financial award but we’ll send you a little treat in the post.

Guest blogger Abdurrahman Pérez (@mr_perez5) discusses his strategies for increasing ‘word consciousness’ in the geography classroom.

What struck me the most while reading Alex Quigley’s (@HuntingEnglish) fantastic ‘Closing the Vocabulary Gap’ (aside from the inspiring reminder of the duty we have to disadvantaged children to better their vocabulary) was the focus on explicit vocabulary teaching. He wants us to make our pupils more ‘word conscious’, and in Episode 13 of ‘The Staffroom’ podcast, he described words as possessing “layers of meaning” and teachers needing to be explicit with students about these when helping them understand specific vocabulary.

Simply put, we cannot just expect them to know, retain and use words magically. We cannot assume. We cannot leave it to anyone else. If you want your pupils to confidently breakdown dense texts, write superb answers to increasingly complex exam questions or to generally be able to understand, analyse and cogently explain (either in writing or verbally) the world around them (as good geographers do), then we need to go about teaching this deliberately. I think some teachers shy away from this – and some say they ‘do not have time to teach vocabulary, isn’t that for English teachers?’ – however, ultimately, it is obvious:

A. You are the expert in the room.

B. Your pupils deserve to be challenged.

Word consciousness

That is why my department and I are focusing on keywords and command words at GCSE and A-Level. In truth, I had begun to do this before reading ‘Closing the Vocabulary Gap’, but anyone who has read it will know that Alex provides you with a thousand and one brilliant practical ways to refine your approach to teaching vocabulary, many of which I’ll take up myself this coming year and use to improve this resource. Without wanting to explicitly make the activity fun – after all, any geography teacher will tell you any and all geography-related content is fun (right?) – it has become a little bit of a game, more so with GCSE actually. I am still developing my A-Level approach so I’ll actually only discuss what I do with my Year 10s and 11s.

The goal of this is that the more familiar your pupils are with key terms (or command words), the more comfortable they are with using them verbally and – most importantly – in an exam setting. Obviously, take that with a pinch of salt, I say ‘most importantly’ simply because this concerns GCSE pupils and I understand a lot of you will not see exam performance as the ‘most important’ thing. Ultimately, you are equipping them with the tools to be able to succeed as geographers – because without a robust vocabulary, they will not be able to communicate their wonderful ideas as well as you want them to.

The aim of the game is simple, identify key terms from their definitions. However, its importance to our approach to interleaving to aid long-term memory and recall, as well as the benefits it has on mock exam/exam question performance is unreal. It has variations, of course, and that’s what the printed cards are for (see Google Drive link below): I can get the whole class to complete a pack (e.g. 3.2.1 Urban Issues and Challenges) with me standing at the front giving clues before the bell rings after we’ve packed away, or I can give a pack to pupil, and they have play Articulate with their partner, or I send one pile of cards around the class and we have to get to the person at the back as quickly as possible with only 3 passes – the possibilities are endless. Two things need to stay at the forefront of your teaching whilst doing this, though:

1. Increase the challenge: if they know the words too well after a while, start asking to follow up or probing questions to embed their understanding and fluency with the vocabulary.

2. Do it often: you need to be doing this often but in a planned manner. That way, in an ideal world, your lesson began with the increasingly popular recall Do Now quizzes (e.g. Geog Your Memory, which is @Jennnnnn_x’s I believe?) or the amazing Find it and Fix it (not sure who made this one!) which focused on a variety of past and present topics, and then ends with you picking a set of key terms from the topic you did, say, last half-term and quickly testing your class.

Increase the challenge

Example of increasing the challenge

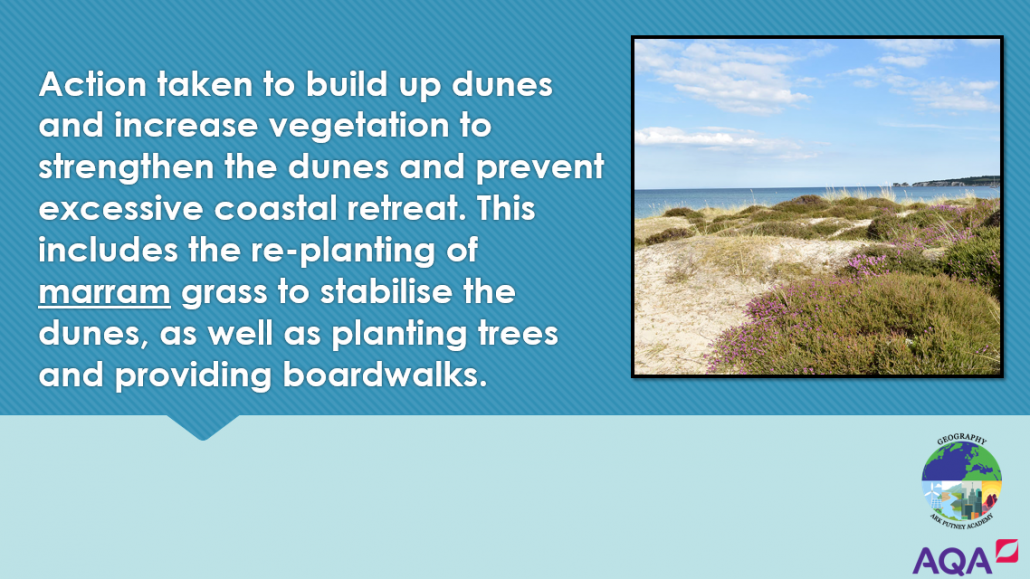

I won’t patronise you – you know this is referring to dune regeneration, one of three soft engineering strategies mentioned in the AQA GCSE specification. Hopefully, in time, your pupils will become bored of the mere sight of this image and definition as they’ll know it so well. But don’t they just know the image? Aren’t they fooling me? Have some even memorised the order and blurted it out in a concerted effort to get me to stop banging on about this and let them go to break?

No… Not if you follow it up. Great stuff, Ali, you know the definition. But I am not stopping there! Please give me a cost of using sand dune regeneration? And a benefit, please? Where was our example of this being used successfully and what was one of the benefits there? Why is sand dune regeneration significant? Who might disagree with its use? Now Ali does not just remember the image or the definition (although you’ve definitely seared that into his mind!), he remembers the rest. If this appears in the exam or if it could be used in the exam, you’ve helped to equip this pupil with the requisite knowledge of the word to be able to successfully ‘apply’ it (the key element of Assessment Objective 3). You will no doubt have got Ali to use this in a practice exam question but having used it verbally with some confidence (after several attempts, if needed – that is fine), he is slowly becoming an expert of this word. Excellent… one down, hundreds to go!

Do it often

I don’t want to launch into an analysis of the evidence behind interleaving, daily/weekly/monthly reviews or cognitive load theory (partly because it is so widespread nowadays), so I will keep this simple: It is well-known that (good) practice makes perfect, so do not use this sparingly. I see my Year 10s twice a week, so I used it twice a week – simple. It’s mostly at the end of the lesson (although, like I said I can and do mix it up) so there’s a little bit of a routine now, mostly because of my consistent use. As I said, I do not just use this – in fact, I think being too rigid will be counter-productive, bore you, bore the kids and not lead to great results. I mix it up with the Keyword of the Day and something a colleague of mine (@watts_education) introduced me to – the A to Z summariser.

What I do repeat, however, is the focus on making the pupils ‘word experts’ and ultimately more ‘word conscious’; by questioning pupils and discussing words/phrases, especially ones like ‘nutrient cycle’, ‘irrigation’ or ‘agribusiness’ which they won’t hear outside your classroom, they will eventually grow more confident. I remember one of my pupils launching into an explanation of orbital eccentricity and the Milankovitch cycle – 5 months after I’d taught it – when another had responded to a question of mine with a puzzled look. I’ll be honest; whatever you think about the quality of your teaching, the first time this vocabulary-focused approach ‘does this’ to one of your pupils, you too will wear a puzzled look.

Hopefully, this technique, along with the necessary probing questioning, which must accompany it, combined with its repeated use, will help your pupils become just a little bit more ‘word conscious’.

Abdurrahman Pérez (@mr_perez5)

August 2019

The AQA GCSE Geography keywords cards are here: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1PFF7PwWKl19wwsjGOSj71qtU4ZaVOhXL?usp=sharing

The AQA A-Level vocabulary is here:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1oMi0u153MA2YN89vD-VghlyT4ocaCICz?usp=sharing

The keyword of the day (adapted Frayer Model): https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/16NpWw2gDtubKsBdj1BL0LFLU0fDIspCV?usp=sharing

A to Z summariser:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1ywNbT5xHp2BOdkkdJE6rz2jfAtYkYAhn?usp=sharing

Internet Geography is offering a platform for guest bloggers for this academic year. Got a teaching strategy, interest or anything geographical you’d like to share? Please contact us. We’re unable to offer a financial award but we’ll send you a little treat in the post.